Although reducing body weight before any surgery is generally a good way to decrease risks associated with surgery, particularly with general anaesthesia, rapid weight loss has another crucial effect beneficial to bariatric surgery (or other abdominal surgery). It will reduce fat and glycogen stores around the liver, making it smaller and softer to work around; therefore, Low Calorie Diet (LCD) is often synonymously known as a Liver Shrinking Diet.

There are a few different ways to go about the pre-op LCD, and the tricky part is to ensure you maximise the nutritional quality of whatever method you use. The chemist, health shop and well-stocked supermarkets usually offer a variety of meal replacement drinks and products that are nutritionally complete. And, of course, many are also available online. Thus, in practical terms, LCD drinks can be easier to ensure you receive the nutrients you need and track your calorie intake to ensure it doesn’t exceed 1000 kcal a day.

The length of time you need to be on an LCD before surgery varies depending on your Body Mass Index (BMI); your consultant will discuss this with you. Generally, if the BMI is at the higher end of the obesity range, your LCD period will be longer than when the BMI is in the lower range. For example, my BMI was 50+++, so my consultant asked me to do an LCD for 4-5 weeks.

I am not going to lie – I was dreading it. Before starting the LCD, I purchased several different products, including Slim Fast drinks and HUEL shakes, and I could not stand any of them or any flavour. And the thought of not chewing for five weeks didn’t appeal to me. So, therefore, I opted for a food based diet, counting calories.

The first few days were awful; the expression ‘hangry’ really applied, but it appeased after 4-5 days and felt much more manageable. The experience was completely different from any other time I’d gone on a diet, this was hard, but psychologically it was easier as it helped to know there was a definite end to it. Also, I’m not planning to ever go on a calorie-restricted diet again as long as I live. I actually relished the challenge of the LCD, and it was encouraging to know I would have better tools to manage overeating after the surgery. My body would work with me rather than against me. Of course, post-surgery, you must adapt to making better and healthier food choices. But the great thing is that there are no ‘forbidden’ foods in principle. Nevertheless, some foods can be more challenging to consume, particularly in the first few months, and you should avoid highly sugary and fatty foods.

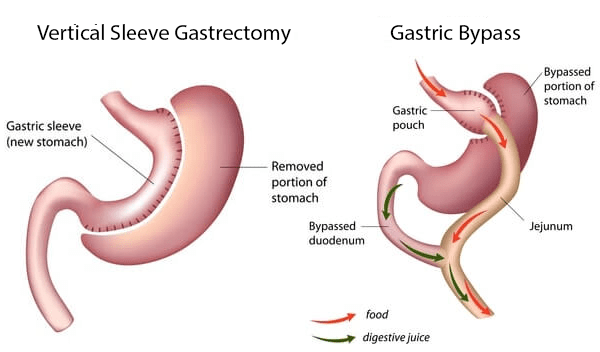

A comforting thought, for me at least, is that it is not like you can’t ever have another piece of chocolate again (I’m a recovering chocoholic 😉). However, you won’t be able to eat much of it, as consuming too much sugar or fatty food can cause dumping*. The beauty of bariatric surgery is that your body will draw your appetite towards healthier, more nutritional food. Basically, the signals between the gut and the brain will be rebooted, upgraded even. It will be easier to understand what your body needs rather than trying to decode corrupted messaging about false appetites and cravings. However, it is probably a good idea to mention that getting used to this ‘new system’ can take some time. You may need up to 12 months to adjust to this new system and adapt to new habits. Because your food preferences will likely change, and you will need to eat smaller portions and more regularly throughout the day, you will need time to implement these changes.

I lost 12kg during the LCD, which was the target the consultant had set for me. Since I was having my surgery abroad and would be staying in Sweden for the duration of my recovery, I was very busy at work leading up to travelling. In addition, I worked from home, so I had only rotated a few different pieces of clothing and not worn many different clothes during the LCD before travelling. When I arrived in Malmö, in the south of Sweden, before my surgery, I changed into clothes I’d not used since the previous winter and found that most of the items I’d brought were extremely loose already. This was a big contrast to my previous experience, where I’d put on clothes I’d not worn for a while, only to find that they were too tight.

That was where my weight loss journey started to kick off. I am currently 13 weeks post-op, and the weight is effortlessly coming off at a steady pace. The enjoyment is that I am not ‘on a diet’.

Before signing off, I would like to emphasise again that using an LCD as a quick way to lose weight is not recommended unless supervised by a health professional. The risks of malnutrition and corrupting your metabolism will likely lead to regaining the weight again and even promote additional weight gain. To understand why dieting is problematic, particularly in people who have been chronically overweight or those living with obesity, please (re)visit my featured blog (Mis)Understanding Obesity.

*” Dumping syndrome occurs when food, especially sugar, moves too quickly from the stomach to the duodenum—the first part of the small intestine—in the upper gastrointestinal (GI) tract. This condition is also called rapid gastric emptying.”

“Dumping Syndrome.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 24 February 2023, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dumping_syndrome.